It’s all in the reflexes.

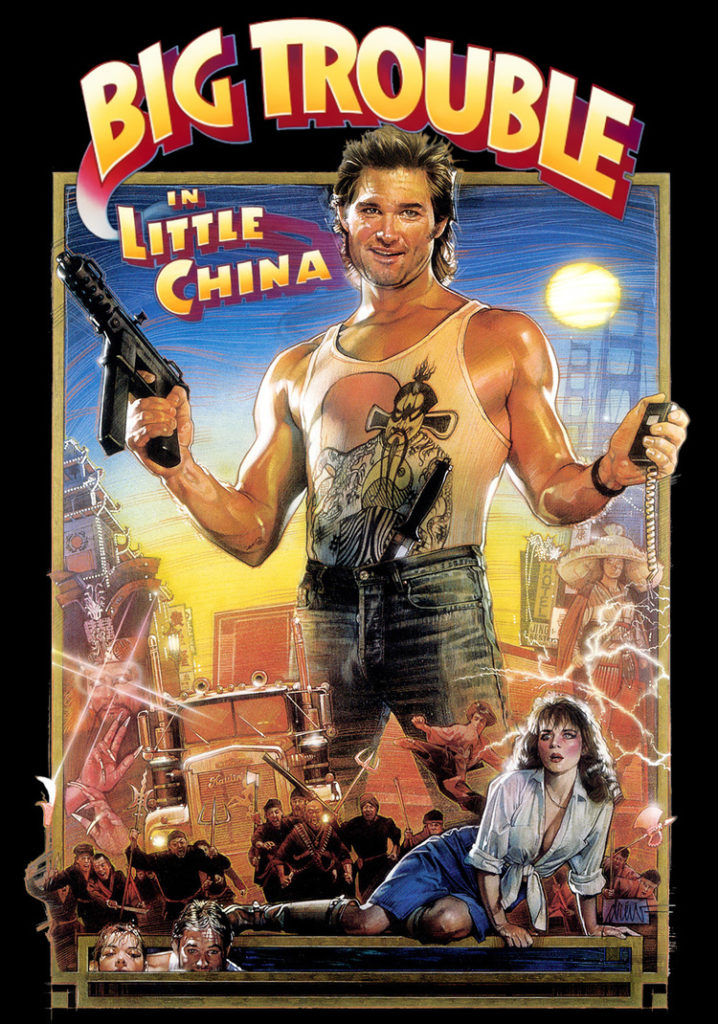

Martial arts films saw a renaissance in the ‘90s when John Woo’s oeuvre found its way from Hong Kong, roughly twenty years after Bruce Lee lit up Hollywood with Enter the Dragon in 1972. Growing up in the ‘70s way before on-demand and YouTube, my generation found their guilty pleasure by watching Kung Fu Theatre on Saturday afternoons. Those intervening years were subdued, with many pale imitators and only a few standouts. Jackie Chan made some noise in the late ‘70s, early ‘80s with Drunken Master and The Big Brawl, but was relegated to cameos in the two Cannonball Run films and stayed on the sidelines until Rumble in the Bronx and Rush Hour made him a superstar. Even Hollywood stepped up to the plate; Chuck Norris made a career pre-Walker: Texas Ranger from martial arts/action films such as Good Guys Wear Black, The Octagon, Lone Wolf McQuade, and Code of Silence to name a few. Tucked somewhere between Chan’s films (with Chan portraying the well-meaning, slightly foolish everyman) and Norris’ (as the testosterone-fuelled, macho, All-American tough-guy loner), is 1986’s Big Trouble in Little China, directed by John Carpenter.

Carpenter had two big commercial successes to his credit, Halloween (1978), which gave birth to the slasher film genre, and Escape from New York (1981), a then futuristic sci-fi/actioner. However, many of Carpenter’s films such as Dark Star (1974), Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), The Fog (1980), The Thing (1982), Starman (1984), and They Live (1988) while financially profitable, are now considered cult classics, and Big Trouble is no exception.

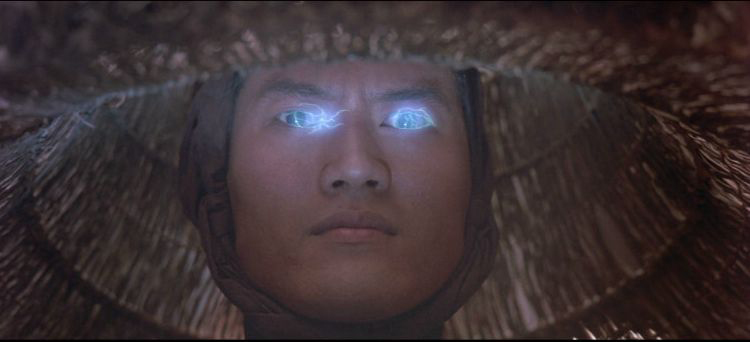

Kurt Russell plays truck driver Jack Burton, who helps Wang Chi (Dennis Dun) rescue his green-eyed fiancée (Suzee Pai) from bandits in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Along with Gracie Lam (Kim Cattrall), they descend into the mysterious underworld beneath Chinatown, where they face an ancient sorcerer named David Lo Pan (James Hong), determined to regain his youth from the sacrifice of the aforementioned green-eyed woman in distress. It’s a thin veil between worlds and Chinatown is right at the proverbial event horizon and exposed to the effects of dark Chinese magic. Lo Pan has at his command the three Storms; Thunder, Rain, and Lightning who appear to have been the inspiration for the Rayden character in the Mortal Kombat video games and films.

Big Trouble has a decidedly Western touch to it; the film was originally set in the Old West where Burton is a cowboy whose horse, not semi truck, is stolen after he arrives in town. The Western has as its core moral tales of good and bad, with the sweeping landscape of the American Frontier in the background. The Hero defending a town against evil or searching for someone lost or abducted are common situations that occur in Westerns and both apply here in Big Trouble. The Loner Hero is very much a Western archetype and represents the constant push West that is the heart of Western mythology. The Western Hero arrives in town, defeats evil, and rides off into the sunset; always on the move, he can’t seem to settle down.

Russell indeed channels John Wayne in his portrayal of Jack Burton; he even slings a saddle bag over his shoulder. But this is a less competent version of The Duke, as Burton is supremely confident in his words, but is clearly outmatched by the situation in which he finds himself. Burton stumbles through fist fights and gun battles, runs scared in one scene and acts tough one minute later, all the while wearing a skeptical, yet somehow nonskeptical look on his face in dealing with the strangeness of Chinese Black magic. He even finds time to hit on Cattrall’s Gracie character at the most inopportune moments, and never wises up as the film progresses. In the final battle he takes himself out of the fight by his own stupidity.

And that’s the gag. Carpenter subverts the Western and action film trope by making Wang the hero and Burton the buffoon, except that Burton isn’t in on it, as he thinks he’s the hero. It’s Wang who knows his way through this world, is able to save the day and get the girl, with Burton riding off into the stormy night in another twist of the Loner Hero archetype. The Burton-Wang friendship is contrary to traditional scenarios in action films where a Caucasian protagonist is helped by a minority sidekick. It is refreshing to see an Asian character perform actions usually reserved for an American hero in an American film, but given the context, it makes perfect sense. Wang’s knowledge of Chinatown, his respect for the dark magic arts, and his great fighting skills better prepare him for what they are to encounter. Victor Wong co-stars as Egg Shen, the Obi-Wan Kenobi-like mentor to Wang and Burton, and a powerful sorcerer in his own right who helps our heroes defeat Lo Pan.

Prior to this film, Kim Cattrall was known for then-raunchy comedies like Porky’s and Police Academy (both are considered tame today), and the 20th Century Fox execs weren’t keen on casting her. It’s a good thing Sex and the City debuted in 1998. Carpenter was adamant to have her in the film as Gracie Law, and his instincts were correct. Cattrall plays Gracie as smart, assertive and fearless, all of which go against the “damsel in distress” type usually found in male-dominated action films. Gracie provides the brains against Burton’s brawn, and she regards him with contempt for most of the film, yet another subversive move from a director who likes to pave his films with plenty of them.

And there’s the rub; the studio didn’t seem to get it. At the time, Carpenter learned that The Golden Child, starring Eddie Murphy, featured a similar theme and was going to be released around the same time as Big Trouble. Turns out Carpenter was initially asked by Paramount Pictures to direct The Golden Child and he passed on it. He stated in an interview with Starlog magazine, “How many adventure pictures dealing with Chinese mysticism have been released by the major studios in the past 20 years? For two of them to come along at the exact same time is more than mere coincidence.” To beat the rival production’s release date in theaters, Big Trouble went into production in October 1985 so that it could open in July 1986, five months before The Golden Child’s Christmas release.

The problem with studio executives is it appears they have no sense of humour; clearly they didn’t understand Carpenter’s way over the top film. It’s almost as if everyone in the film seems to be in on the joke except the execs who write the cheques and who didn’t want an over the top film. In an interview with Ain’t it Cool News, Carpenter recalls the studio didn’t know how to market or release it, so they insisted that “we write something, so we came up with that scene with Victor Wong and the lawyer talking about what happened. All they wanted to hear Victor say was, “Jack Burton is a man of courage.” They thought that would explain everything to the audience.” What the executives didn’t realise was that that move actually made the film funnier, making their wishes even more absurd.

In the DVD commentary, Carpenter stated that the reason 20th Century Fox did little to promote the film was because they didn’t know how to. Big Trouble opened on July 2, 1986 and grossed $11.1 million domestically against a budget of $25 million. It likely didn’t help that Big Trouble was released in the midst of the hype for James Cameron’s Aliens, which hit cinemas two weeks later.

Reviews were mixed. Carpenter became disillusioned with Hollywood and became an independent filmmaker. He told Starlog, “The experience [of Big Trouble] was the reason I stopped making movies for the Hollywood studios. I won’t work for them again. I think Big Trouble is a wonderful film, and I’m very proud of it. But the reception it received, and the reasons for that reception, were too much for me to deal with. I’m too old for that sort of bullshit.” Prince of Darkness (1987) and They Live (1988) were made independently through Alive Films, free from studio interference, and distributed by Universal Pictures.

Mixed reviews and fair to middling box office tallies haven’t stopped Big Trouble from becoming a cult classic on home video. Kurt Russell said in an interview with A&E’s Biography series that (at the time) in every Blockbuster Video he walked into Big Trouble was the only one of his films that never stayed on the shelves. That seems to be the truer litmus test of a film’s staying power – at least it used to be. Perhaps nowadays it would be measured by how many downloads it gets, legal or otherwise. Big Trouble in Little China doesn’t take itself seriously, and neither should we; it’s a film one looks back on with fondness, when as teens we were large storms of hormones and awkwardness, and had the words of Jack Burton to guide us through:

“You just listen to the old Pork-Chop Express here now and take his advice on a dark and stormy night when the lightning’s crashing and the thunder’s rollin’ and the rain’s coming down. Just remember what ol’ Jack Burton does when the earth quakes, and the poison arrows fall from the sky, and the pillars of Heaven shake. Yeah, Jack Burton just looks that big ol’ storm right square in the eye and he says, ‘Give me your best shot, pal. I can take it’.”

This article was originally published in Issue 7 of Comix Asylum Magazine (July 2014).