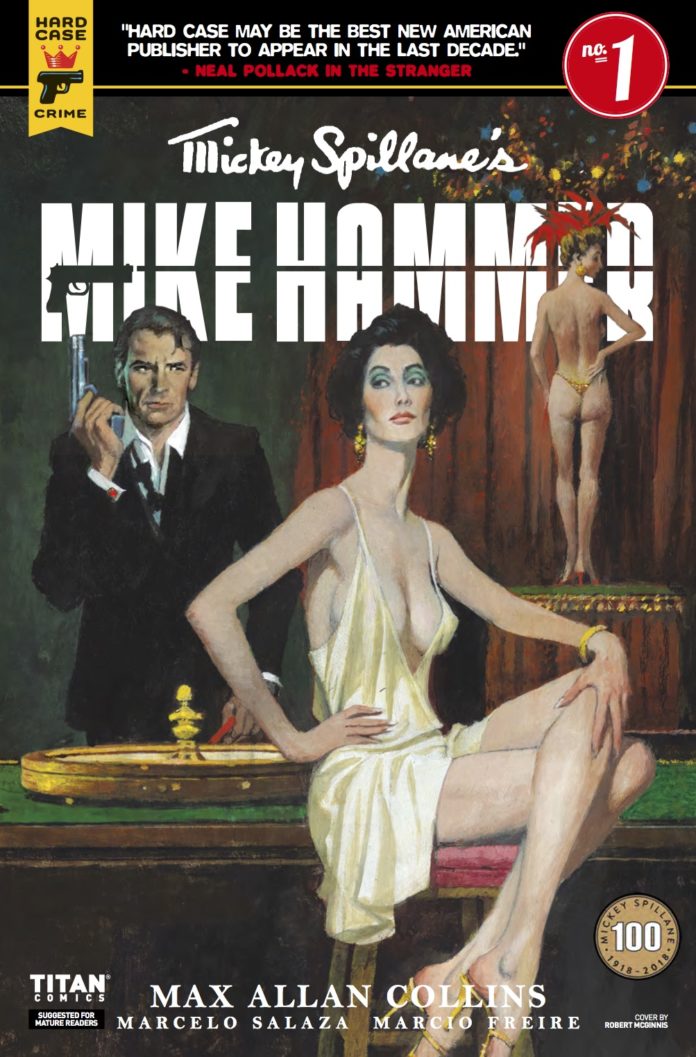

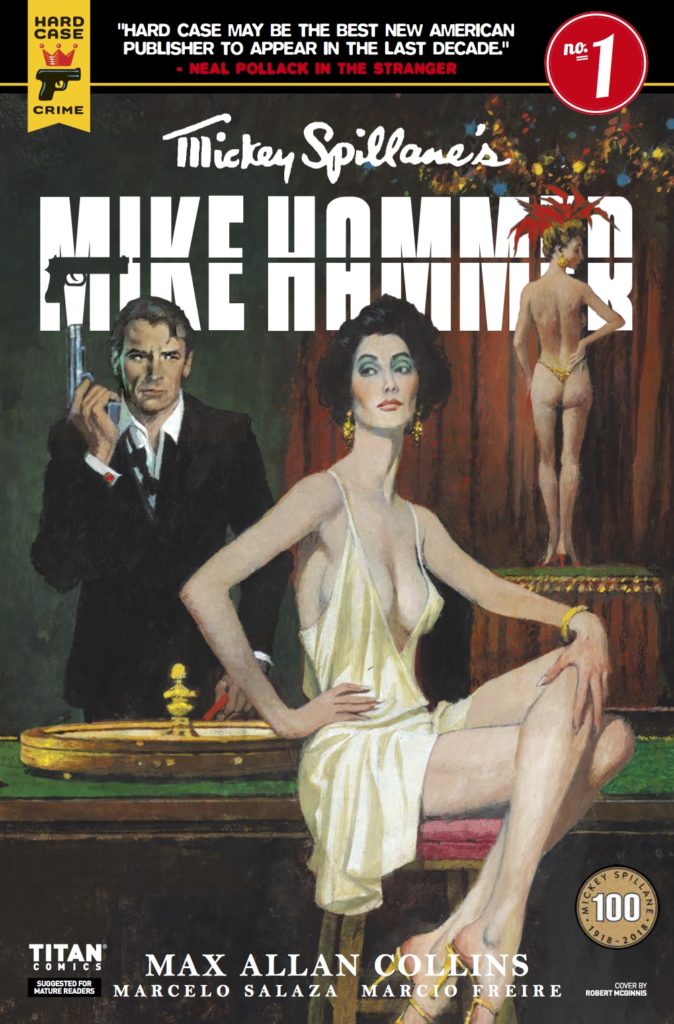

Mickey Spillane’s tough-talking, brawling, skirt-chasing private detective Mike Hammer returns to comics in this thrilling noir series, based on an original plot by Mickey Spillane, written by Max Allan Collins.

Mickey Spillane’s tough-talking, brawling, skirt-chasing private detective Mike Hammer returns to comics in this thrilling noir series, based on an original plot by Mickey Spillane, written by Max Allan Collins.

Hard-boiled is not just a type of cooked egg; this sub-genre of crime fiction features world weary, cynical private detectives dealing with corruption and violence in both the criminal underworld and a legal system that is supposed to seek justice for all. Sam Spade, Phillip Marlow and Lew Archer are such notable antihero private detectives, and now we have the return of another from Titan Comics in Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer.

Funnily enough, the Mike Hammer character began his life in a comic book. Spillane was an established comic-book writer, and in 1946 he worked with illustrator Mike Roy to create the private-eye character Mike Danger for proposed comic-book or comic-strip publication. Spillane was unable to sell the project as a comic, so he reworked the story as the novel I, the Jury, converting Mike Danger to Mike Hammer and supporting character Holly to Velda.

Unlike his hard-boiled contemporaries, Hammer is very much a hard man; with a general contempt for people, Hammer is brutally violent and fuelled by a genuine rage against violent crime that never seems to affect Raymond Chandler’s Marlowe or Dashiell Hammett’s Spade in quite the same way.

While gumshoes like Marlow and Spade bend and manipulate the law, Hammer often views it as an obstacle to dishing out justice, ironically the one virtue he holds in absolute esteem. He nevertheless respects the police, realizing they have a difficult job and are frequently handcuffed by the law when trying to stop criminals.

The Washington Times obituary of Spillane said of Hammer, “In a manner similar to Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry, Hammer was a cynical loner contemptuous of the ‘tedious process’ of the legal system, choosing instead to enforce the law on his own terms.”

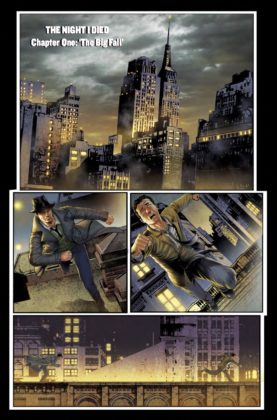

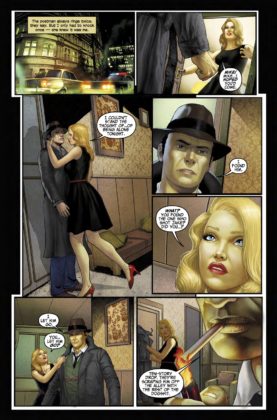

This brings us to the first issue of the new Mike Hammer comics – Chapter 1 of The Night I Died. A chance encounter with a captivating femme fatale leads to a violent mob retaliation, and Mike Hammer finds himself dodging both bullets and hard broads as he undertakes the most dangerous case of his career.

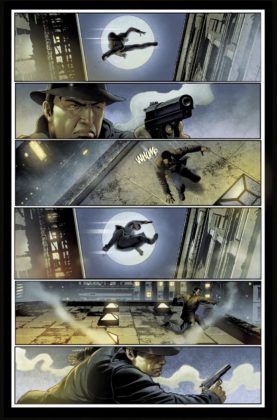

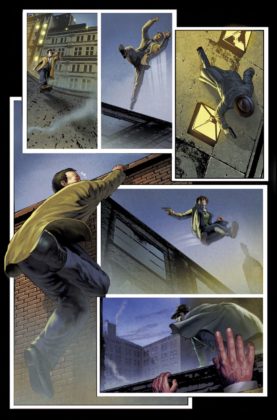

The story is told in first person, and we ride alongside Hammer as he chases down criminals and introduces them to his .45 automatic. A far as the violence is concerned, the comic doesn’t pull punches; people get shot, dropped from rooftops and burned alive. Note I said people; women aren’t immune from the violence that inhabits Hammer’s world.

The art and colouring (Marcelo Salaza and Marcio Freire respectively) are what you would expect from a pulp detective story; a certain grittiness, Dutch angles, rain, and lots of shadows and darkness that eschew the glossy look of many a comic. It’s as if you are watching events unfold through the thick plume of cigarette smoke, and there’s enough here to make Don Draper envious, or at the very least be convinced the comic was sponsored by Camel, Marlboro, or Chesterfield.

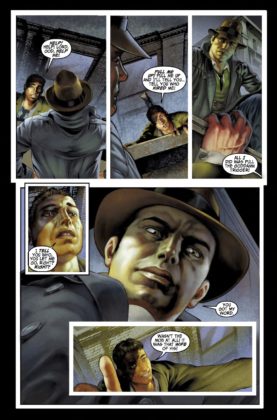

Also present is the narration, a mental play-by-play which Hammer gives in short, choppy sentences with little conjunction but heavy on the metaphors and similes which are in stark contrast to the simple vocabulary – the bread and butter of good private eye monologues. I read the comic and imagine Hammer speaks to me in a deep, chain-smoker baritone, not unlike Stacy Keach, who played Hammer in the 1980s CBS series.

Hammer punches, pistol-whips, and shoots his way through a meeting that turns sideways because of a “broad”, as Hammer says, and that’s only chapter one. Femme Fatales and Broads inhabit this world, complete with come hither looks, pencil skirts, and legs that would make a gazelle jealous. Men are rugged and scarred; no one would mistake these guys for members of a boy band.

Mike Hammer is typical of the tough-talking, hard-nosed, detectives that were born in a certain era. The comic is unapologetically masculine, and I wonder how the comic might fare given 21st century sensibilities and recent events with the #MeToo movement. It raises the question of can a work of fiction be read and enjoyed as a product of its time and context or do successive generations have the right to view the material with the lenses they interpret media. Perhaps there is room for both schools of thought; else literary scholars would be out of business.

That said, I enjoyed the first issue of Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer and look forward to reading more as they are published. Hopefully I don’t dodge any bullets taking on the most dangerous case of my career.